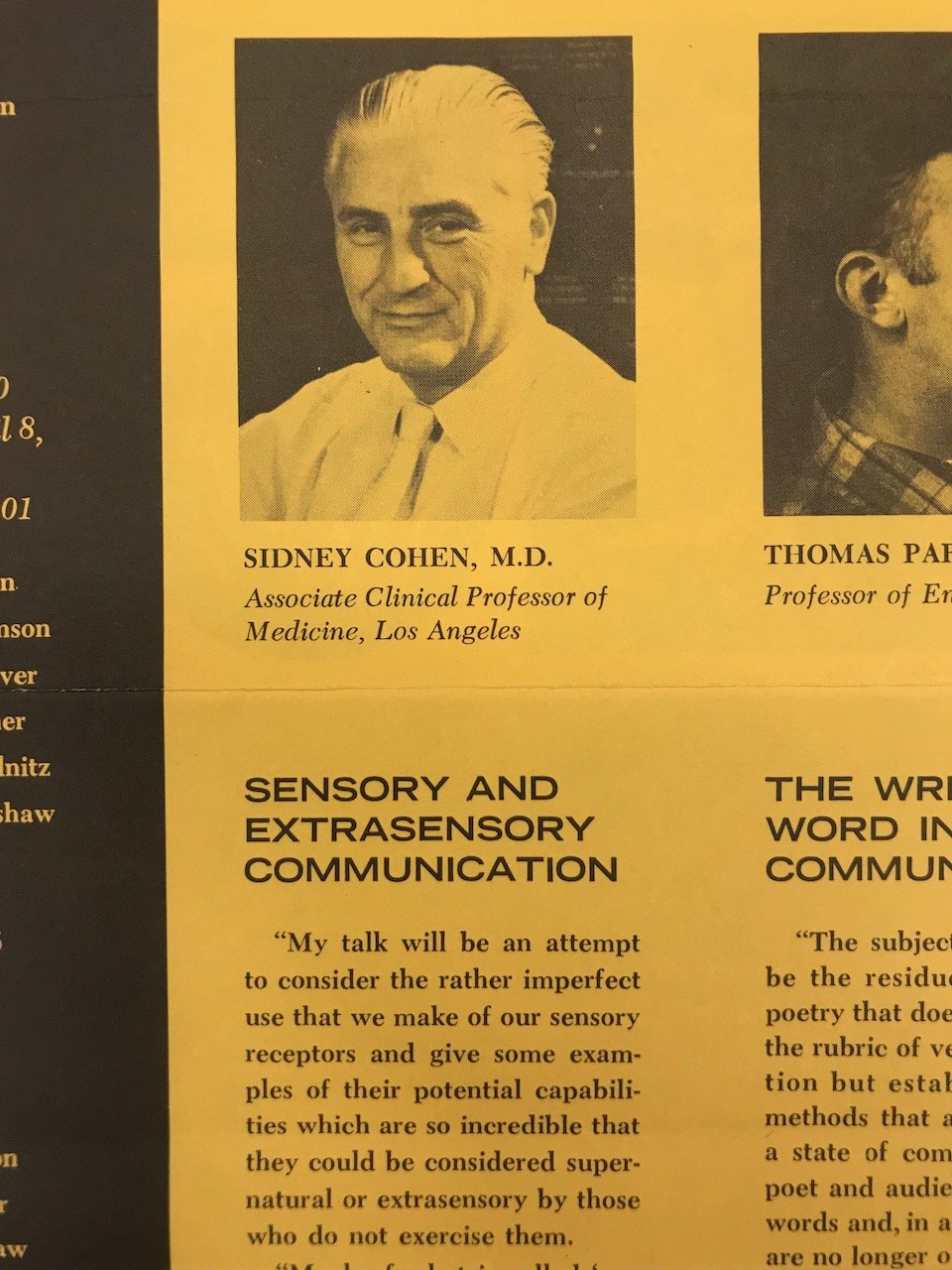

1965: Sidney Cohen’s UCLA Speech on ESP

Author: Sidney Cohen

Date: February 24, 1965

Source: Archives of the UCLA Communications Studies Department.

Partial transcript

“There is a group of drugs, the hallucinogens, which permits us to experience anesthesias even at ordinary intensities of sensation. Under the influence of drugs like LSD, mescaline, psilocybin, and so forth, the subject may speak of the patterns which sounds produce, the scent of music, even the effect of a change of mood upon the colors that are seen.

But to get back to dermal optical perception, what should we believe now on the basis of the available reports? Those of us who are less critical and who are quite readily ready to accept new notions might be inclined to say that dermal optical perception is a fact. At the other extreme, I'm sure there's a group who are highly cautious and who change their established beliefs with some difficulty. They'll say it's impossible or it's a trick.

It seems to me that neither attitude is ideal. The first tends to make us gullible and we come to believe much that turns out to be nonsensical. The second closes our mind too tightly to entirely new constructs. As a result, we might miss the periodic shattering of our belief system which seems to be a part of living, especially in this century.

I would submit that in instances of this sort, dermal optical perception being only an available example, that we keep a suspense file. Items are put in there which are possible, unproven, and that we keep open to many notions but wait for other evidence. It would seem best to be neither credulous nor incredulous. This might mean that most of our beliefs, especially such eternal questions as ‘What am I?’ and ‘What does it all mean?’ and so forth, would have to be put into the suspense file, and remain a permanent one.

This is true. We appear to know little for sure. Many of our beliefs, especially those oddly enough most tightly held, are based upon faith, not proof. We're only two or three centuries into the rationalistic, mechanistic Scientific Revolution. It began as a result against superstition, ignorance, and stubborn dogma. It was embraced by those who wanted to know nature by test, not testament.

The history of science is replete with new laws overthrowing old established ones as knowledge accrues. The old theory becomes less and less tenable. Finally, someone propounds a new paradigm which is a better explanation for the data than the prevailing one, and it's accepted. Well, not all scientists, those advocates of reason and new ideas, change their minds in the face of irrefutable evidence. All too often, they do not.

Copernicus was called mad by his colleagues because he stated that the earth moved when patently it did not. His work was not accepted for almost a century after his death. For a while, no one would even look through Galileo's telescope. Newton met with a similar dogmatic rejection during his lifetime. Priestley never did relinquish his phlogiston in favor of Lavoisier's oxygen theory. Lord Kelvin, who contributed much to physics, called x-rays a hoax and Maxwell's electromagnetic theory nonsense.

Both Darwin and Planck predicted that their views would not be accepted until their contemporaries died off, and they were right. Resistance to a major reconstruction of long-held scientific views is by no means invariable. Witness the rather rapid acceptance of Einstein's revolutionary ideas. It does remind us, though, that scientists are human and tend to have emotional investments in their established beliefs. They are apt to be as rigid and closed to the new as anyone else. This should not be surprising, except that we idealize a scientist as being open-minded and willing to entertain constructs with which he does not agree. This is probably less true than we imagined.

This diversion into belief systems is by no means a straying off the track. Concepts come before percepts. We cannot see what we cannot conceive. When a new paradigm is adopted, the person looks at the old percepts in a new way. Uranus was seen at least 17 times by various observers and called a star. Finally, after a hundred years of sightings, Herschel insisted that it had planetary movement. This was after all the planets had been discovered, you know. After that, everyone saw it as a planet. So as you see, even sensory communication is valuable, especially when the communication has an emotional charge to it.

And so we come to the third part of the talk today, the issue of extrasensory communication. I disagree with Chancellor Murphy when he says that I have some particular knowledge of this field. Really, I can only claim to have done one minor little experiment in this area. This was a number of years ago and it was done in connection with some other work that was ongoing. It was an attempt to stabilize the phenomenon of extrasensory perception with drugs.

One of the annoying things about extrasensory perception is that it's not quite reliable. It isn't reproducible, and one wondered whether drugs like lysergic acid diethylamide might perhaps help fix it in those who had it or keep it away from those who didn't. Well, we simply had our subjects sort Rhine cards. I'm sure you all know what Rhine cards are. They're also called Zener cards. They had one of five different figures on them: star, cross, and so forth. And we asked our subjects to sort them into piles while sober and then while under the influence of lysergic acid.

I might report that they did no better under LSD than they did before they took the drug. But that is of no great consequence. It was a small series and had no particular meaning. Other drugs have been used for the same purpose. The Russians have used mescaline, alcohol has been used, barbiturates, stimulants, and so forth. To date, oddly enough, the drug which gives the best results is alcohol.

I merely relate this brief incident to be perfectly honest with you as to my qualifications in this matter. However, I was forced into it and I have done some homework, and I'd like to talk with you about my impressions of the extrasensory perception literature.

Just in case there is anyone here who's dubious about what extrasensory perception or parapsychology or the psi phenomenon is, let me immediately say that it ranges from the transference of thoughts by non-sensory means, which is telepathy, to the ability to obtain information from inanimate objects, which is clairvoyance, to the ability to influence inanimate objects, which is psychokinesis, the capacity to know events before they occur, precognition. And this goes on to very recondite matters such as automatic writing, glossolalia or the ability to speak in tongues unknown to the subject, reincarnation with the ability to remember something of the previous existence, and communications with the departed via a medium.

One of the first things I discovered in wading through this literature was that there were two kinds of parapsychologists, just as there are no doubt two kinds of scientists. There was what might be called a square parapsychologist who uses scientific methods to design his experiments. He uses a very approved statistical treatment of the results and very rigid controls. These could be epitomized by such people as Rhine and Pratt, Smiler Murphy. By the way, three or four, three of those four will be here in June, and many others.

Then there are the further out parapsychologists who are rather contemptuous of efforts to scientifically prove these paranormal phenomena by using scientific criteria of predictability, reproducibility, the ideas of the physical transmission of energy and, of course, effect relationships. Actually, these two groups dislike each other more than they dislike the scientists.

Well, I'm not qualified to evaluate the evidence of what might be called parascientific parapsychology. These are the anecdotes, narrative reports of poltergeists, astral projections, discarnate entities who communicate with the living through mediums, possessed personalities, ectoplasmic apparition, psychic healing, and so forth. I've read a good deal of the material, it's fascinating. I can only say it takes an act of faith, not of reason, to believe in these matters, and I'm not diminishing it by saying this. There may be things that are not amenable to the rational, reasonable mind. In fact, I'm sure many of you believe there are.

Some of these occult events seem to border a bit upon the psychopathic, but not necessarily so. The mere fact that some of the practitioners are obviously fraudulent does not necessarily condemn the entire literature on these esoteric occurrences.”

Cohen delivered versions of this talk on ESP throughout 1965 and 1966; this summary is from a pamphlet in the Clare Luce Boothe papers at the Library of Congress.

📕 For more on Sidney Cohen, see his Biography page.